Strong as Steel

Written by Rashid Faisal

July 12, 2022

In 1911, Cornelius L. Henderson became the second African American to earn an engineering degree from U-M. He was a pioneering steel engineer and architect who helped construct two of the major Great Lakes crossings between the United States and Canada.

by Rashid Faisal

Born in 1887 or 1888 in Detroit, Cornelius Langston Henderson’s intellectual and educational foundation was laid by his father, the Reverend Henderson, a scholarly and educated man.

The elder Henderson had earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Oberlin College, another master’s degree from Wilberforce University, a Doctor of Laws degree from the Detroit College of Law, and a Doctor of Divinity degree from Payne University. His occupations included minister of the historic Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Detroit; lawyer; and president of two African American colleges: Morris Brown College in Atlanta, Georgia; and Payne University in Selma, Alabama.

Cornelius Henderson spent many of his formative educational years on the campuses of Morris Brown and Payne. After graduating from a pre-college program at Payne in 1906, he enrolled at the University of Michigan to study civil engineering. He was the lone African American student in the entire engineering department.

Henderson was the beneficiary of the leadership and vision of U-M President James B. Angell, who had expanded the university’s curriculum to include studies in engineering and architecture. Henderson and his fellow students fulfilled degree requirements by completing courses such as structural mechanics; strength and resistance of materials; theory and analysis of structures; structural design; and hydraulics, mechanics of fluids, and hydraulic motors.

As the university’s only African-American engineering student during an era of both de facto and de jure segregation, Henderson was forced to work in isolation as he grappled with complex mathematical and engineering principles. He did not receive the academic and social benefits of working with a partner or in study groups. As a result, one of Henderson’s professors remarked that he possessed a much better knowledge of engineering and architecture than did the other 34 graduating seniors because he “had to learn his work without help.”

After graduating from U-M in 1911 with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering, Henderson began looking for employment in Detroit.

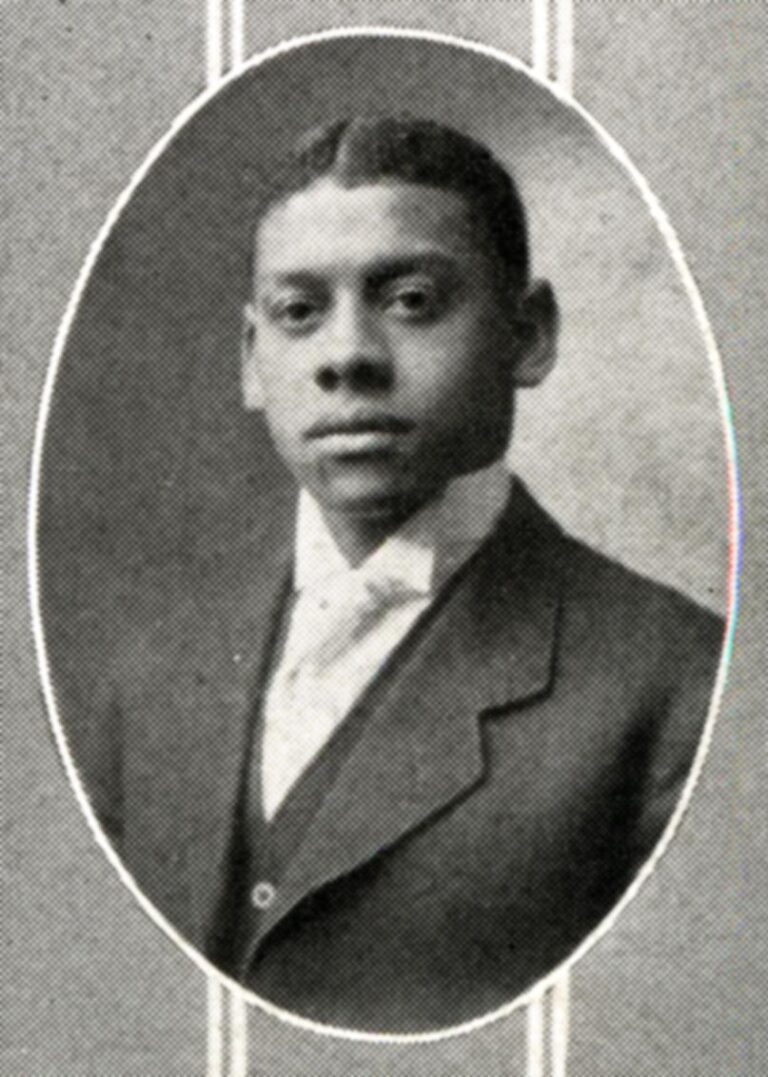

Cornelius Henderson's senior portrait, 1911.

Woodward Avenue on a rainy night in Detroit, circa 1920. Wolff Family Photo Collection, Bentley Historical Library.

Despite enjoying the distinction of being U-M’s second African-American graduate in the field of engineering—the first was Frederick Blackburn Pelham, class of 1887—he struggled to begin a career. Engineering jobs were plentiful, and Henderson demonstrated strong aptitudes in mathematics, steel construction, and architectural design, but companies refused to hire him because of his race.

Cornelius Henderson Jr., Henderson’s son, remembered his father’s determination to secure employment as an engineer despite racial discrimination: “He didn’t talk racial-wise. Nobody much talked racial-wise. They knew it was hard to get jobs, but you just went out there and did what you had to do to get a job.”

As fate would have it, Henderson crossed paths with a fellow student from his undergraduate days at U-M, B.K. Bash, a 1909 graduate of the university’s engineering department. Remembering the young, talented, lone AfricanAmerican engineering student who was forced to study in isolation, Bash encouraged Henderson to apply to the company where he worked, the Canadian Bridge Company (CBC), located across the Detroit River in Walkerville, Ontario.

The CBC was an Ontario-based engineering firm that specialized in manufacturing steel trusses and cables used in bridge construction. The company was owned by Willard Pope of Grosse Pointe, Michigan, who had graduated from Detroit’s Central High School and U-M. Pope organized the CBC with Francis Charles McMath and went on to serve as the company’s vice president and chief engineer.

Henderson recalled the fateful day that changed the course of his life: “One day I was downtown and happened to meet one of the few classmates who would talk to me. He informed me that the Canadian Bridge Co. in Windsor was searching for someone with my qualifications. Therefore, I applied and, to my surprise, acquired the position.”

Henderson remained with the CBC for 47 years, retiring in 1958. First hired as a draftsman in the company’s drafting department in 1911, Henderson quickly worked his way up the ranks by demonstrating a high degree of technical competence.

By 1917, he had become manager of the stock department, and he was further elevated to steel cost estimator in 1920. He worked in that capacity until 1928, when he was promoted to structural design engineer.

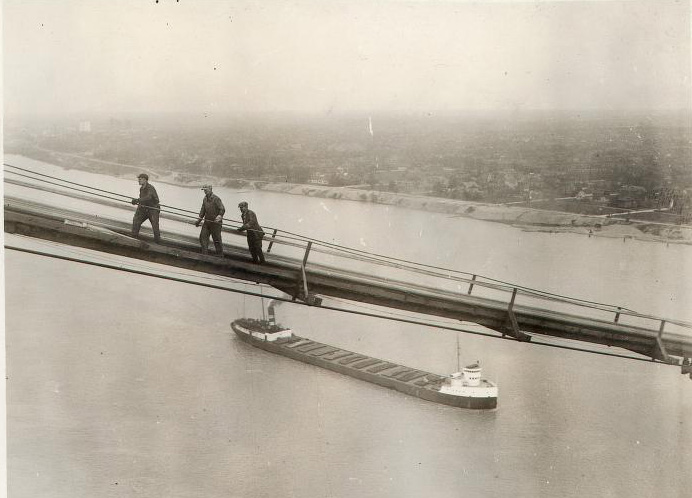

During his career, Henderson proved himself an exceptional engineer and architectural designer, taking on numerous projects throughout Canada, the United States, and the rest of the world. His most noteworthy accomplishment took place in 1927, when the CBC won a lucrative contract to build an international bridge across the Detroit River to link the cities of Detroit and Windsor and commemorate American and Canadian soldiers who had served in World War I.

Construction of the Ambassador Bridge lasted from the summer of 1927 to the fall of 1929. Henderson, who was appointed chief structural steel designer for the Canadian side of the international project, first designed the Windsor approach to the bridge and later supervised the installation of many of the bridge’s steel sections.

On November 11, 1929, the Ambassador Bridge was officially completed at a total cost of $23.5 million. Four days later, more than 150,000 drivers lined up to cross what was, at the time, the longest suspension bridge in the world. The bridge had a center span of 1,850 feet and a total length of 7,490 feet, or nearly 1.5 miles.

Unfortunately, Henderson’s contributions to the design and construction of the Ambassador Bridge have gone largely unknown and without record. Nevertheless, he contributed a great deal to one of both the United States’ and Canada’s busiest international crossings.

Ambassador Bridge construction workers, circa 1928. William Christian Weber Papers, Bentley Historical Library.

Henderson’s engineering and architectural accomplishments extended well beyond his work on the Ambassador Bridge. During his 47-year career with the CBC, his advanced skills in structural steel design made him a highly sought after civil engineer. He worked on building railroads, highway bridges, lift bridges, municipal buildings, factories, residences, cemeteries, apartment buildings, and more throughout the United States and Canada. He also worked on engineering projects around the world, in places such as the Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand, and South America.

After the completion of the Ambassador Bridge, Henderson contributed to the construction of the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel, which was an extraordinary feat in engineering ingenuity. Started in 1928, the tunnel was officially dedicated on November 1, 1930, by President Herbert Hoover. It was the world’s first international underground vehicle tunnel and only the third underwater highway constructed in the United States. Henderson is credited with serving as construction supervisor of the steel tubes enclosing the 5,160-footlong passageway.

Early construction of the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel. William Christian Weber Papers, Bentley Historical Library.

Some of Henderson’s other famous projects include the Thousand Islands and Quebec Bridges over the Saint Lawrence River between New York and Ontario and the vertical lift bridges over the Welland Canal to connect Lakes Ontario and Erie in Ontario.

He worked on commercial building projects for the Dominion Forge & Stamping Company; Dominion Iron & Steel Company; General Motors Corporation of Canada; Ford Motor Company of Canada; Chrysler Corporation; and General Electric Company. He also contributed to the building of the Canadian Supreme Court Building, hangars at the Royal Canadian Air Force Station Trenton; and the headquarters of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Henderson lent his architectural and engineering skills to the construction of two of Michigan’s great international crossings—the Ambassador Bridge and the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel—and a host of other massively important projects across the country and throughout the world.

When he died on July 23, 1976, in Detroit, it was only fitting that he be buried at Detroit Memorial Park, a cemetery that he, too, helped found and design.

Categories: Uncategorized