African American Student Housing in Ann Arbor

Written by Andrew Rutledge

June 22, 2022

Finding housing was often a challenge for African American students at U-M. It was not until 1915 that the first dormitories—for women—were built on the campus and, prior to that, all students had to find places to live in local boarding houses. These houses became significant culturally and socially.

144 Hill Street

This eight-bedroom house still stands at the corner of Hill and Green Streets. It was one of the most prominent homes for African American students attending Michigan for nearly six decades. Between 1900 and 1960, more than 250 Black students made their homes there.

Central to the story of 144 Hill Street was Esther Dickson, who owned and managed the building for nearly 50 years. Born in Canada, she came to Michigan as a child in the 1860s and eventually followed her son, William, a law student from 1902-03 and then a medical student from 1907-11, to Ann Arbor. She soon began renting her home to students. Perhaps due to her son’s presence, she initially rented only to male students.

Esther continued renting rooms after William’s graduation and, in the fall of 1920, two-dozen African American students decided to form a house club centered at 144 Hill. The group dubbed itself the Monon Club, taking its name from Monon, Indiana, which was an important railroad hub. The Club received official recognition from the University and included members of both the Alpha Phi Alpha and Omega Psi Phi fraternities. It lasted through 1924.

Esther Dixon, second from right, with students circa 1937.

In the late 1920s, Esther decided that she would rather board female students. Her decision coincided with a move by the Women’s Advisory Council to create a University-approved League House for “colored girls.” Prior to this, they had been living in scattered homes around Ann Arbor. 144 Hill was approved for the 1928-29 school year but proved unpopular due to its distance from campus and location next to the railroad tracks. The experiment was abandoned, and the University established a house at 1102 Ann Street instead.

Esther continued providing rooms for both male and female students for another two decades. She also provided lodging to African American travelers and was the only Ann Arbor home listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book. The house continued after her passing, providing a home for Black students through the 1950s.

The house at 144 Hill Street still stands today.

1009 Catherine Street and 420 Fourth Avenue

1009 Catherine Street not only provided a place to live for nearly 300 African American students during the early 20th century, it also became a center for the Black community in Ann Arbor more generally as the home of the Dunbar Community Center in the 1930s.

In the early 1900s, the property was owned by Kentucky-born Edward J. Lewis, who worked as a cook in the University hospital. By 1910, he and his wife were also renting out rooms to male African American students at the University. Although the numbers fluctuated, between five and ten students would call 1009 Catherine their home every year for the next two decades. The house was also the site for meetings of the Negro-Caucasian Club, the first interracial student association at Michigan.

A concert inside Dunbar House, undated. Image courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library.

In 1930, the Lewises sold their home to the Dunbar Civic Center. Organized in 1923 by Reverend Ralph M. Gilbert and named for the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, the Center’s original purpose was to provide or assist in locating housing for Black laborers working for the railroad and for Black University of Michigan students. By 1930, however, the Center had expanded beyond the capacity of its original location at 420 Fourth Avenue. Its new location at 1009 Catherine, the Center continued to provide housing to Black students and also greatly expanded its programming as a social services organization. It distributed clothing to the needy, aided the unemployed in finding work, created a lending library, and hosted weekly meetings for a variety of groups in the Ann Arbor Black community.

All this activity, however, made the 1009 Catherine location increasingly insufficient. In 1937, a new property was purchased at 420 North Fourth Avenue and the Center relocated again. The house on Catherine returned to private ownership and the new owners continued to rent rooms to Black students, primarily graduate students, until the early 1950s.

The Dunbar Center's third home after 1937 was 420 North Fourth Avenue.

1017 Catherine Street

The two-story house at 1017 Catherine Street near Glen Avenue provided lodging to African American students for more than 50 years. And in April 1909, it witnessed a significant moment of Michigan history when six Black students gathered there to form a chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, the first African American Greek organization at the University of Michigan.

Located at the eastern end of the predominantly African American old Fourth Ward in Ann Arbor, the house on Catherine was owned by J. F. Schaible in the early 1900s. Schaible rented it out to Black students appreciative of its location near both central campus and the University hospital.

In late 1908, at the request of medical student William Thorne, one of those boarders, Augustus A. Williams, wrote the Alpha Phi Alpha chapter at Cornell asking how “a body of fellows” in Ann Arbor could become affiliated with the fraternity. Upon receiving a positive response, Williams and five of his friends, including George Ellison, the first African American member of Phi Beta Kappa at Michigan, formed the Epsilon Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity. When the renowned scholar W.E.B. DuBois visited Ann Arbor in 1909, the members of Epsilon Chapter initiated him into the fraternity at the house.

Students on the steps of 1017 East Catherine in 1910.

In 1910, Dalia MacDonald became the new owner of the property and she allowed the fraternity to remain in the house and even to sell services out of the building. For example, one brother was allowed to work as a barber.

However, in the 1911-12 academic year, the $100-per-month rent became difficult for the fraternity to continue to pay. After a series of negotiations, the decision was made to seek another home, which was reinforced by MacDonald’s death in May 1912. In the fall of 1913, Alpha Phi Alpha moved to 1340 Volland Street.

Both male and female African American students would live at 1017 Catherine for another 40 years. In the late 1950s, however, the house was sold to Saint Joseph Mercy Hospital and was demolished in 1963. Today, the University of Michigan Hospital’s Glen Avenue Parking structure stands at the site.

1017 Catherine Street circa 1911.

1102 East Ann Street

The wood-frame house that stood at 1102 East Ann Street was one of the most important locations in the history of African American students at the University of Michigan. From 1931 to 1945, “University House Number 2,” as it was formally and euphemistically known, was the primary residence for Michigan’s Black female students and a major social hub for all African Americans at the University. In that period, more than 300 Black students lived in the house.

In the late 1920s, concerns arose among University administrators over issues in housing female African American students in deeply segregated Ann Arbor. These concerns involved not only the refusal of many landlords to rent to Black students, but also a desire to keep them out of the new Mosher-Jordan residence hall.

After an experiment with a private lodging house at 144 Hill failed, it was decided to renovate the University-owned building at 1102 East Ann for them. Administrators were careful not to declare that the house was specifically for Black students or that they were required to live there, only that they were “welcome” to live there.

Opened for the 1931-32 school year with 13 women, the house was overseen by the Michigan League and managed by Alice Benjamin, who served as the house chaperone, cook, and informal adviser. The three-story house had room for nearly 20 students at a price of $63 per semester for a shared room or $72 if one wanted their own space. Three meals were provided every day, with two on Sunday. The “B house,” as it was commonly known, swiftly became a social hub for African American students with numerous notices in The Michigan Daily about meetings, “get-acquainted” receptions, and other events at the house.

Following a car accident that left her seriously injured Alice Benjamin retired and Anna E. Smith became the new house manager in 1937. She was succeeded in turn by graduate student Roberta Ellis Britt in 1944. In the summer of 1946, the house was razed to make way for the new Food Service Building for the dormitories and a new location for Black women was established at 1136 East Catherine.

1102 East Ann Street, undated.

1103 East Huron Street

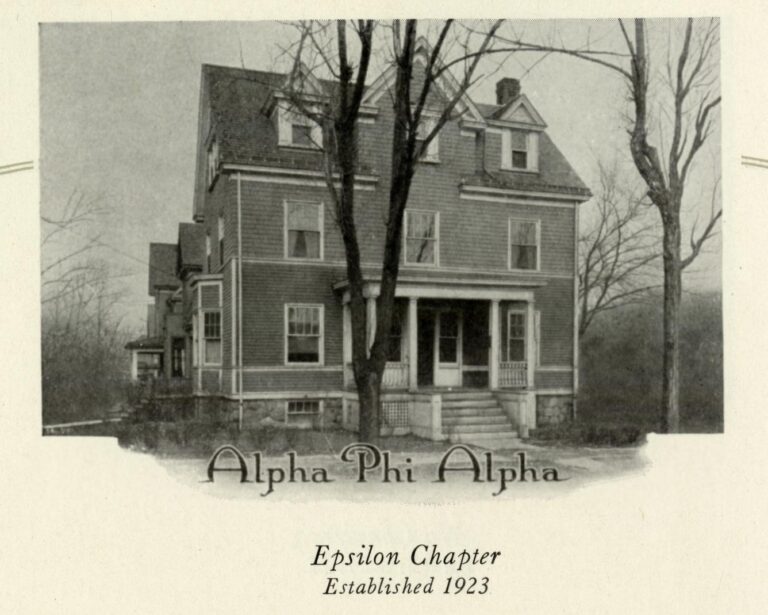

The three-story frame house at 1103 East Huron Street served as the first true Black fraternity house at the University. From 1923 to 1936, the brothers of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity made their home there.

The Epsilon Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha was founded in 1909 by Black students living at 1017 Catherine Street, but over the next 15 years they had no permanent home, shifting between rooming houses across the city. In 1923, however, its members found a new location on East Huron and made their home there for the next 14 years. The house itself was poorly insulated and its residents did much of their studying in the library or at the Union in order to save on heating costs. Most worked as waiters at white fraternity houses to earn money and to secure meals.

Nevertheless, 1103 Huron provided a haven for Black students from segregated student life at Michigan. Fraternity meetings and initiations were held there, along with frequent all-night house poker parties. Additionally, every spring, the fraternity organized an elaborate house party for its members. Because there were so few Black students attending the University, members brought dates from Detroit, Ypsilanti, and even Chicago, surrendering the house for their use the weekend of the parties. They also hosted speakers, such as University President C.C. Little, who visited in 1928.

For unclear reasons, though perhaps due to finances, the 1935-36 school year was the last Alpha Phi Alpha spent at 1103 Huron. The house changed hands to the white Psi Omega dental fraternity, while Alpha Phi Alpha was not listed in city directories as having another house for 15 years.

1103 East Huron Street, the Alpha Phi Alpha house.

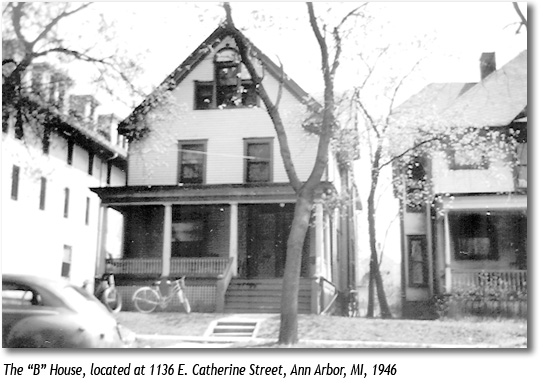

1136 Catherine Street

The three-story house at 1136 Catherine Street was the successor to the house on 1102 East Ann Street as a home organized by the University for female African American students to live. For the decade between 1946 and 1956, more than 120 Black students, mostly graduate students, lived there.

In 1931, the University opened a house at 1102 East Ann for female Black students who had difficulty finding housing elsewhere in Ann Arbor and who were informally discouraged from applying to live in the dormitories. In 1946, that house was demolished and a new house was established at 1136 Catherine Street.

The house had room for 17 women in 10 bedrooms with kitchen privileges and was overseen by a graduate student, Roberta Ellis Britt, who lived on the ground floor with her husband. The structure was not designed to host so many lodgers; according to a housing inspection on behalf of the Dean of Women, it had only one “bathroom, containing one toilet, two washbowls and one bathtub” for residents and no fire escape. Such was its state that an emergency was declared for the 1950 spring term, and its residents moved to the dormitories while improvements were made.

Despite these issues, the house was also a prominent social site for African American students with the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority hosting gatherings there. The house softball and basketball teams were active participants in the Women’s Athletic Association. The house remained in use until 1956, when it was demolished for hospital expansion.

1136 Catherine Street, image taken from the Ellis Family Story.

1345 Geddes Avenue

The two-story house at 1345 Geddes Avenue was where seven Black football players, the highest number in a single recruiting class the University had yet known, made their home from 1970 to 1972, dubbing it “The Den of the Mellow Men.”

In the fall of 1968, seven African Americans arrived in Ann Arbor to play football. The seven—William “Billy” Taylor, Glenn Doughty, Thomas Darden, Reggie McKenzie, Michael Oldham, Michael Taylor, and Butch Carpenter—formed an instant bond and were soon branding themselves “The Mellow Men.”

The “Mellow Men” at their campus home, 1971.

The following year, they were key contributors to new Michigan coach Bo Schembechler’s first team. After that season, and two years living in the West Quad dormitories, the group decided to rent an apartment together. But University policy required athletes to live in dorms, so they concocted a plan to lie to the Athletic Director that Schembechler had given them permission to rent a house on Geddes. If the truth was ever known, they were never punished, and the “Den of the Mellow Men” became their home.

The seven would gather to discuss world and campus issues almost every night, and while they were famous for their parties, they had rules as well. Every Friday they would clean; as Billy Taylor would recall, “the house was a wreck for six days, but we wanted it nice for Saturday because that’s when our parents would visit after the game.”

And there was much to celebrate on Saturdays; during their three years on the varsity team, the athletes would help guide Michigan to a 28-4 record and two Big Ten championships.

The Mellow Men were famous, and their achievements—and their Den—were celebrated both in Michigan and in national sports journals such as Sports Illustrated. Six of the seven would go on to play in the National Football League.

1345 Geddes Avenue still houses U-M students today.

1702 Hill Street

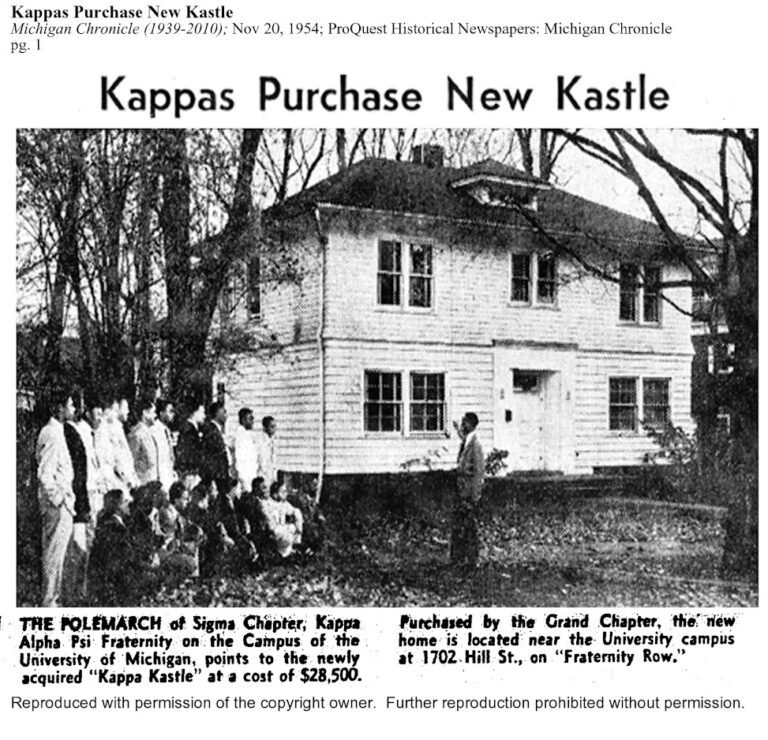

The two-story clapboard house that stood at 1702 Hill Street was the first home owned by an African American fraternity at the University, when Kappa Alpha Psi’s Sigma Chapter purchased it in 1954.

Sigma Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi had its origins with the Kappa Club formed in 1922, but when its members first applied for formal University recognition as a fraternity the following year, they were denied due to their “poor scholastic standing.”

Nevertheless, the brothers persevered, hosting events and pledging new members. The small numbers of Black students at Michigan meant that its membership was always small, however, and the chapter died out twice in its early years. Sigma Chapter was re-founded and recognized by the University in 1931 and again in 1947, with graduate students who had pledged elsewhere before coming to Ann Arbor sparking both renaissances.

Like other Black Greek organizations at Michigan, Kappa Alpha Psi lacked a house of their own and held events in the Michigan Union or in the apartments of its members. In 1954 that changed, when the fraternity’s members purchased the house at 1702 Hill for $28,500 to serve as their “Kappa Castle.”

The six-bedroom house became the fraternity’s new home and, as the only house owned by an African American Greek organization at Michigan, quickly came to be a focus of Black students’ social lives, with parties and dances held there. One of its most famous residents was basketball player Cazzie Russell, who as a fraternity brother stayed there during his junior year. Tired of the constant parade of visitors seeking to meet him, he quietly moved out his senior year in 1966, even as the house’s residents grew to more than two dozen brothers.

Unfortunately, 1702 Hill required constant maintenance and costly repairs. As early as 1968, the fraternity had expressed interest in potentially leaving and, by the early 1970s, they had sold it, once again spreading their members out across Ann Arbor.

1702 Hill Street from the Michigan Chronicle, 1954.

632 Fourth Avenue

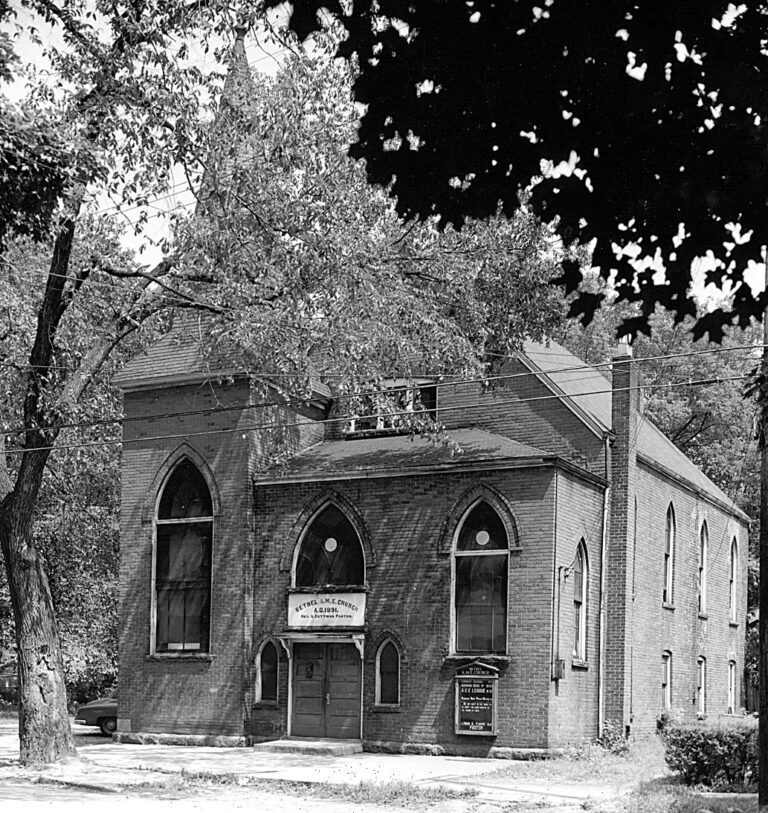

The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church was the first independent Black church in the United States. Founded in Philadelphia in 1794, the Church spread across the country. The first congregation in Ann Arbor was organized by John Wesley Brooks, a former enslaved person from New York who came to Washtenaw County in 1829 to farm.

In the 1850s, Brooks helped establish the Union Church at 504 High Street, which served Ann Arbor’s Black residents. The Church opened its doors in 1857 to two congregations: the African Baptist Church (later known as Second Baptist) and the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. In the early 1870s, however, a split occurred within the African American religious community.

The AME congregation left the Union Church and began to worship on the east side of Fourth Avenue between Summit Street and what is now Beakes Street, across the street from Brooks’ house. In 1891, construction began on a larger church building at 632 North Fourth Avenue. Completed in 1896, Bethel was ideally situated to provide its congregation and the city’s growing African American community with services that went well beyond being a place of worship. The church hosted outdoor dinners in the summer for the neighborhood and offered space for meetings and clubs.

Black students at the University not only attended services at Bethel as individuals, but Black Greek organizations also held events there. For example, in 1932 the members of Kappa Alpha Psi arranged for a professor in the Sociology Department to speak on the “Responsibility of College Men to Society,” while in the 1940s, Omega Psi Phi held its annual National Achievement Week events at the church.

In 1971, the congregation moved to a new church on Plum Street (now John A. Woods Drive, named after the Rev. John A. Woods, who oversaw the move), where it continues to hold services to this day.

Bethel AME Church, image courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library.

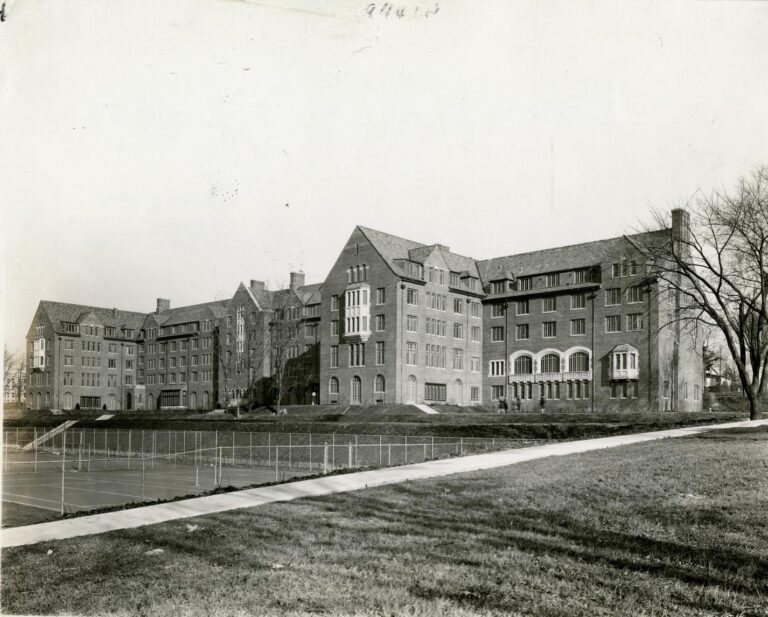

Mosher-Jordan Hall

In 1930, the University of Michigan prepared to open the doors to its first dormitory, with space for 450 female students. Even though at least two Black students had applied to live there, every one of its inaugural residents was white. It took more than a year of activism by Black students, their parents, and alumni before Mosher-Jordan Hall opened its doors to African Americans.

As the number of female students at Michigan grew in the early twentieth century, the shortage of housing grew more acute. Several small university-owned residences were created in the 1910s and 1920s, but those were not enough. As a result, in September 1928, the Board of Regents adopted a proposal to construct a dormitory that would house more than 400 women just east of the Women’s Athletic Field. The building would be named Mosher-Jordan Hall in honor of the University’s first two Deans of Women, Eliza Mosher and Myra Jordan.

Even as it was being built, charges of racism were levied at the dormitory. Two Black students, Helen Rhetta from Baltimore and Vivian Wilson from Washington, D.C., had applied for residence in Mosher-Jordan, but had not heard any response, despite the fact that white classmates were being accepted. Newspapers, such as The Baltimore-Afro American picked up the story, reporting that instead Rhetta was directed to the all-Black women house at 1102 East Ann.

Charles Roxborough, Michigan’s first African American state senator, learned of the situation and wrote a resolution calling for a formal investigation into discrimination at the University. Agitation by Rhetta Roxborough and others succeeded in causing the University to change its unstated and unofficial policy of segregation. In 1931, six African American women applied for rooms, and two were accepted, though only one—E’Dora Morton of Detroit—would live there.

Although Mosher-Jordan Hall was now open to Black students, relatively few lived there over the following three decades. Most female African American students still lived in private housing or the house on East Ann.

On average fewer than a half dozen Black students, including Roxborough’s daughters, lived in Mosher-Jordan each year. It was only in the 1960s, as Michigan’s Black student body grew, that a growing number of Black women a year were able to take advantage of the victory against segregation 30 years before.

Mosher-Jordan Hall, circa 1930.

909 East University Avenue

Muriel Lester House is a cooperative house and part of Michigan’s Inter-Cooperative Council. Founded in 1940 and inspired by African American student Jean Fairfax and white student Josephine Rouse, it was the University’s first explicitly inter-racial and inter-faith women’s housing unit.

Fairfax and Rouse were both members of the Methodist Church and were inspired to form their own all-women’s cooperative by the pre-existing Michigan cooperative housing movement, particularly the Methodist men’s co-op Stalker House. A house was duly rented at 909 East University Avenue for the 1940-41 school year and was named for Muriel Lester, an English social reformer and pacifist. When it opened in September, nine women lived there including Fairfax and another Black student as well as several Jewish and white students. Originally, several Japanese students had planned on living there as well, but the threat of war caused them to return to Japan.

As a cooperative house, residents worked six hours a week on various house duties as well as attending house meetings, where decisions were made democratically about policies, food, and other issues. In return, they paid substantially less for room and board than they would have at a more traditional boarding house.

To further offset expenses, Lester House obtained permission from the Dean of Women to have male students dine at their house for a fee—the first co-ed eating at Michigan. Jean Fairfax was the driving force behind all these developments, while a University-approved house mother provided counseling and oversaw the residents’ behavior. After two years, a new house was selected at 1002 Oakland Avenue and, in 1943, the Saturday Evening Post published a lengthy story on Lester House as emblematic of the broader cooperative movement on university campuses.

The members of Lester House frequently invited speakers to discuss social issues, particularly those related to equality, and were active in efforts to combat discrimination such as protests against Ann Arbor restaurants that refused to serve Black customers. In 1951, a campaign was launched to purchase a new home for the co-op at 900 Oakland Avenue, where it remains to this day. In the 1960s the house was opened to male students.

The Muriel Lester House at 909 East University Avenue.

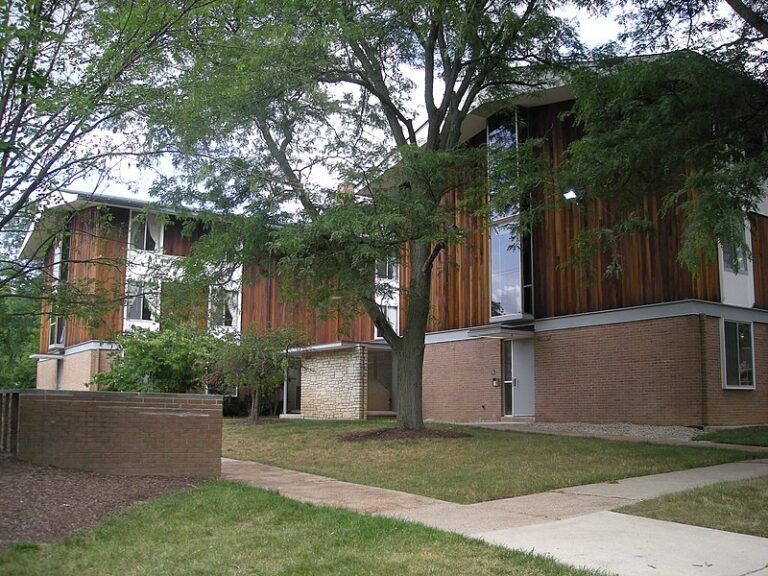

Oxford Housing

Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha are the two oldest African American sororities at the University of Michigan, founded in 1921 and 1933 respectively. However, neither had a house for their members until 1968, when the two groups petitioned the University Housing Office for space in the Oxford Housing complex.

Like other African American Greek organizations at Michigan, Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha struggled from their foundation with issues of membership and housing. The relatively small numbers of female Black students at the University and the lack of financial support from larger national organizations meant that neither sorority was able to purchase a house for its members. Instead, meetings and events were held in the Michigan League or in the residences of individual members. The lack of a central meeting place for members of the two chapters made communication more difficult and curtailed much of the social experience that Greek life offered in other sororities.

In January 1968, the two sororities, with the support of the Panhellenic Association, petitioned the University Housing Office that they each be granted a house in the Oxford Housing complex for the 1968-69 academic year. Although there was opposition from some residents and the University policy had been not to provide housing to student groups, the Regents approved the proposal using the argument that the two chapters would be applying for rooms as individuals and that the offer was “a gesture to make the University more attractive to Opportunity Award students and to Negroes.” Twenty-two sisters of Delta Sigma Theta moved into Goddard House that September, and 29 sisters of Alpha Kappa Alpha into Vandenberg House.

The co-operative housing system of Oxford proved unpopular with the women, however. The work requirements proved burdensome and others disliked the University-appointed resident directors. As a result, nearly half of Delta Sigma Theta’s members moved out before the school year ended and the sorority did not remain for a second year. Alpha Kappa Alpha remained for the 1969-70 year in smaller numbers, but after that the sorority left as well.

The experiment in University-supplied sorority housing was ended and the sororities’ members once again spread across campus.

Oxford Housing complex, image courtesy of Wikimedia.

Second Baptist Church

The nation’s first Black Baptist Church was founded in the 1780s in Savannah, Georgia. In the following decades, free African Americans in both northern and southern cities formed their own Baptist congregations.

In Ann Arbor, this occurred in 1865 when a small group of worshippers gathered to worship at the Union Church at 504 High Street. The Church was shared with the city’s African Methodist congregation for several years, but following a split in the 1870s, the Methodists left for their own building.

In 1890, the Baptist congregation began worshipping at a new church at 216 Beakes Street. It also renamed itself as the Second Baptist Church to distinguish itself from the predominantly white First Baptist Church that already existed.

As an early sign of the Church’s connection with the University, President James Angell was invited and agreed to give “words of good cheer” at the laying of the new church’s cornerstone in 1888. And indeed, Second Baptist provided a spiritual home to generations of Black students at Michigan, with its Sunday services listed in The Michigan Daily for decades.

The congregation also provided space for African American students to meet and host events; for example, it was at a church meeting that a group of Black and white students formed the Negro-Caucasian Club in 1925, the first inter-racial student association at Michigan. Omega Psi Phi fraternity had a particularly close relationship with Second Baptist, holding their annual Memorial Day events there, beginning in the 1930s, in which they honored notable African Americans who had passed away in the previous year.

In 1980, Second Baptist moved again to a new building at its current location on Red Oak Road, where it continues to offer services and community to this day.

Second Baptist Church, image courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library.

922 Woodlawn Avenue

Up until the 1960s, the heart of Ann Arbor’s African American community was the “Old Fourth Ward,” which today is known as Kerrytown. But there were other areas of the city where African American residents clustered in the segregated city. One of those was the one-block section of Woodlawn Avenue, stretching from Packard Street to Sheehan Avenue, a half mile south of the University campus.

Beginning around 1930, several Black families purchased homes on this street and offered rooms to students. Hundreds of Black students lived there over the next three decades, and 922 Woodlawn was one of the most popular addresses, offering a home to more than 130 students over two decades.

In 1934, James J. Johnston, an African American who managed an antique store downtown, purchased the house at 922 Woodlawn and soon began renting the house to Black graduate students during the summer months. One of the first to stay there was Theophilus McKinney, Dean of Johnson C. Smith University in North Carolina, who was pursuing graduate work at Michigan. Johnston welcomed around a dozen students to his home annually, mostly men, but also some women such as the Virginian Marian Wall who lived there with her husband Limas Wall in the summer of 1938.

Johnston ceased renting to students in the late 1940s, but nearby homes such as 945 and 947 Woodlawn continued to rent to African American students until the late 1950s. Other Michigan students purchased homes on the street; for example, in 1939, Ph.D. student Wade Ellis purchased a home with his brother Francis, a master’s student, for $4,000. Their extended family lived there with many attending Michigan during the 1940s, and then in the 1950s they too rented rooms to small numbers of Black graduate students.

As efforts to fight discrimination in housing gained strength in the late 1950s, new housing options opened for African American students closer to campus and the numbers living on Woodlawn declined to almost none.

922 Woodlawn Ave. as it stands now in Ann Arbor.

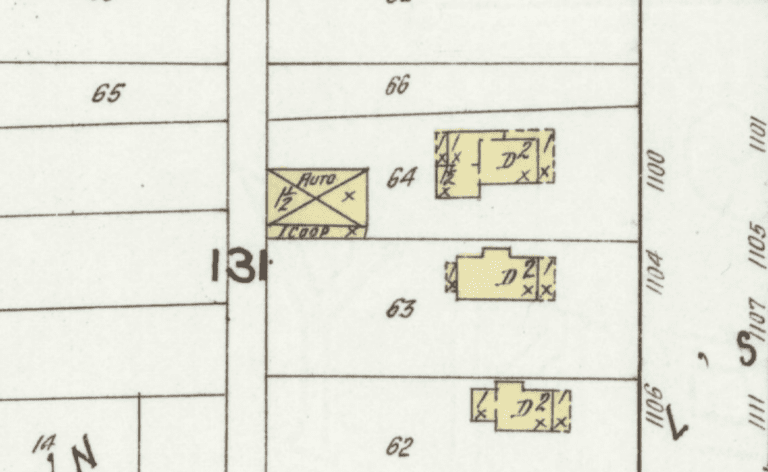

1102 Lincoln Ave.

The vast majority of African American students who attended the University of Michigan in the first half of the 20th century lived in Black neighborhoods in Ann Arbor, such as the modern Kerrytown district. Some, however, lived in homes located in predominantly white areas such as 1102 Lincoln Avenue in Burns Park.

In 1902, George Craig, a Black liveryman, purchased the frame building located on an alley behind Lincoln Avenue to be a combination family home and stable. With the exception of a single neighbor, the area was entirely white-owned and occupied.

Almost immediately, the Craigs began renting their spare room to Black students attending the University, with law student Guy Milton from Kansas being the first. For the next 20 years, between one and three students would live there every year. Most were undergraduates such as Craig’s daughter Jessie, but the house also proved popular with students at the homeopathic hospital, including Julius Bowley, who stayed there from 1910 to 1913.

George Craig sold the property in 1923, and that year the house was occupied by members of Phi Chapter of Omega Psi Phi fraternity. Chartered the previous year, the chapter was the second recognized African American fraternity at Michigan, and its founders made 1102 Lincoln their first fraternity house. During the 1923-24 school year, eight of its 11 members lived at the house, including William Dehart Hubbard, who would become the first African American to win an Olympic gold medal in an individual event, the long jump, at the Paris games the following summer. In 1925, 1102 Lincoln was torn down and the lot merged with its neighbors.

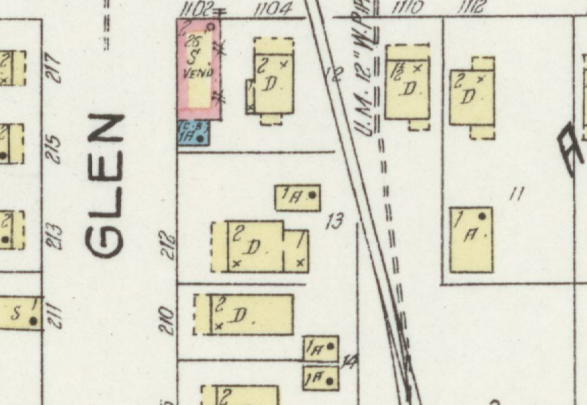

The 1916 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows 1102 Lincoln in an alley and denotes it as also serving as a stable.

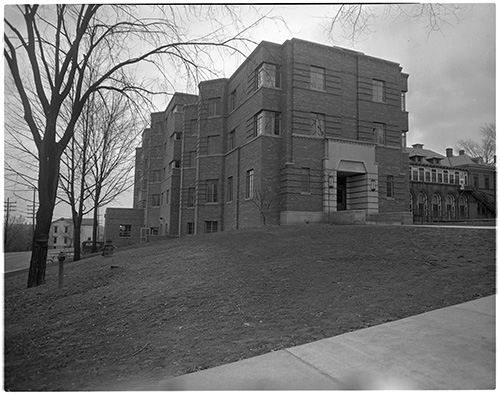

Fletcher Hall

Fletcher Hall was conceived by a group of Michigan alumni in the early 1920s as a privately owned dormitory. The building was sold to the University in 1933 and became the first University-owned men’s residence hall. With a brief break in the 1950s, it would serve as a men’s dorm for the next forty years.

Named for former Regent Frank W. Fletcher, the building was built in 1922 with space for 124 male students in double rooms. The building proved unprofitable to the builders, however, and the situation was made worse by the onset of the Great Depression and the police uncovering of a bootlegging operation run by residents in 1929. In 1933, the University purchased it and halved the number of students living there. The first African American resident was Harold Bailer in 1938.

For the next several years, a number of Black graduate students stayed at Fletcher during the summer terms. A single room cost $20, compared to $30 for other dorms. After World War II, several African American undergraduates lived there as well, most notably Charles Fonville, who lived there four of his five years at Michigan, including the year he set the world record in shot put.

During the latter part of the 1950s, Fletcher was converted to a women’s dormitory for several years, and seven or eight African American students lived there every year. By 1960, it returned to being an all-men’s dorm and remained that way into the 1970s. It was the last dormitory on campus to admit female residents.

Fletcher Hall in this undated image from the Alumni Association records, HS9281.

Victor Vaughan House

Built in 1939 with the aid of the Works Project Administration, the Victor C. Vaughan House was designed as a dormitory for first-year medical students with the first Black student admitted in Winter 1940. It served this purpose through World War II before housing shortages caused the University to convert it to undergraduate housing. From 1951 to its closure as a dormitory in 1962, it housed female students, a number of whom came from outside the U.S.

Michigan’s Board of Regents approved a plan for a dormitory for medical students in June 1938 using private funding and support from the Federal Works Project Administration. With room for 139 students at 1111 Catherine Street overlooking the Huron River, the building was completed the following year and named for former Dean of the Medical School, Victor C. Vaughan. The first Black medical student to live in the dorm was Frank Perryn Raiford Jr. in 1940. He would be joined by several other Black students during the war.

In 1943, the building was turned over to the armed forces for housing army medical students. Among those who arrived in September of that year was James Lee Curtis, who would go on to an accomplished career in psychiatry.

With the return of peace in 1946, Michigan found itself facing a major housing shortage and the decision was made to convert Victor Vaughan House into an undergraduate dorm. In 1946, it was designated a women’s dorm, but for the next several years it returned to providing housing for male students. Beginning in 1952 it was again a women’s dormitory and would remain one for the next decade. Among those who made it their home in that period were pharmacy student Anna Lucretia Sherman from Liberia and Cleo Shakespeare, a graduate student in social work who would go on to research educational organization and innovation.

In 1963, the building was remodeled as a classroom and office building, and it continues as the latter to this day.

Victor Vaughan House in 1939, image courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library.

210 Glen Avenue

Since the mid-1800s, the small Ann Arbor area bound by Fuller Road, Catherine Street, and Glen Avenue was a nearly all-Black neighborhood. It was also one of the poorer areas of the city, with almost 50 percent of its buildings in deteriorated condition by 1960. Nevertheless, its proximity to Michigan’s campus made it a popular area for African American students to live. One of the most popular addresses was a three-bedroom home at 210 Glen Avenue, where, between 1906 and 1960, more than 300 students lived.

The first African American student known to have lived at 210 Glen was Mabel Harper in 1906. For the next 15 years, the house was largely a home for international students, with residents forming a chapter of the Hindusthan Association of America in 1917. Black students returned in the 1920s and, in 1922, seven lived there during the school year; two others during the summer term. These students were undergraduates including Eugene Perry, president of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, and William DeHart Hubbard, future Olympian, and graduate students including Chester Chinn, a medical student from Rhode Island. The summer students were all graduate students.

For most of this time, 210 Glen was owned by a widow named Cecelia Fort, a Black woman who first came to Ann Arbor from Canada as a cook. The house hosted around 10 students every year, with tragedy striking in 1944 when a Ph.D. student living there drowned during a canoeing accident on the Huron River. Beginning in the 1950s, the number of Black students at the house declined to only a handful a year. 210 Glen continued to offer rooms to students until 2008, when the University purchased the property and demolished the house.

The 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows a home at 210 Glen Avenue. It was demolished by U-M in 2008.

Categories: Uncategorized