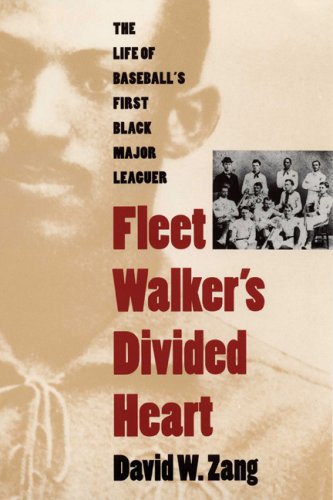

Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart: The Life of Baseball’s First Black Major Leaguer

Long before Jackie Robinson, Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first African American to play professional baseball in the major leagues, playing for the Toledo Blue Stockings in the 1880s.

If you ask most Americans the name of the first Black player in Major League Baseball, they will likely say Jackie Robinson. But there was another African American in the major leagues almost a century before: Moses Fleetwood Walker. In this fascinating biography, David Zang recounts Walker’s life, charting its connections with the hardening of “scientific” racism in the late 1800s that ended the halting movement towards integration of the post-Civil War era and destroyed Walker’s baseball dreams.

Born in Ohio in 1857, Walker fell in love with baseball as a student at Oberlin College, playing on an integrated team on a campus that was nearly 10 percent Black. He transferred to the University of Michigan in 1882 in order to study law, escape Oberlin’s condemnation over his fiancé’s pregnancy, and to play baseball. He succeeded at two of those, but never finished his law degree.

He left Michigan in 1884 to play professionally for the Toledo Blue Stockings, but despite his skill, he suffered numerous racist insults and discriminatory incidents from both teammates and spectators. The team went bankrupt after the season, and Walker spent several years in minor leagues before being driven from baseball permanently. By then, alcoholism and anger were growing parts of his character and, in 1891, he killed a man in a drunken fight. Although he was acquitted, he was arrested again a few years later, this time for mail theft.

Returning to Ohio, he became increasingly disillusioned about the prospects for Blacks in America, eventually penning in 1908 what Zang describes as “the most learned book a professional athlete ever wrote.” In Our Home Colony, Walker drew on the racist “scientific” theories of the time to advocate that all African Americans should return to Africa, dismissing any possibility for cooperation or even coexistence between whites and Blacks. Spending his last 20 years as a part-time inventor and theater owner, Walker died in 1924.