Detroiter and Olympian Eddie Tolan

Written by Rashid Faisal

November 29, 2022

Eddie Tolan made history and broke barriers as a Black athlete. Today, his medals and a pair of his shoes are on display at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, and a field is named in his honor. His triumphs were never easy, especially when he returned to Detroit at the height of the Great Depression.

by Rashid Faisal

Born on September 29, 1908, in Denver, Colorado, Thomas Edward “Eddie” Tolan Jr. entered the world one month after the Springfield race riot in Illinois led to the formation of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Indeed, Tolan and his family would experience the hardships of living in a racially polarized society—one plagued by violence, segregation, political disenfranchisement, and limited socioeconomic mobility for most of the Black population.

The Tolan family—led by his father, Thomas Edward Sr., and his mother, Alice—relocated to Salt Lake City, Utah, before moving to Detroit, Michigan, in search of stable employment during the summer of 1924. Tolan Sr. also hoped that the Motor City would provide his children—June, Martha, Hart, and Eddie—with access to quality schools.

Tolan’s High School Career

Tolan and his brother, Hart, enrolled at the predominantly white Cass Technical High School in 1924, which had a stellar reputation for preparing graduates for college or immediate job opportunities in Detroit’s industries. Eddie Tolan held professional aspirations, hoping to become a doctor or lawyer.

Athletically gifted, Tolan excelled at football, baseball, and track. His favorite sport was football, and he joined the Cass Tech team in 1924, seeing limited duty as a backup player. By the following season, Tolan was the starting quarterback. The athlete combined lightning quickness; catlike evasiveness; and a powerful, accurate arm that led Cass Tech to a victorious 12-6 season.

Although Tolan’s athletic ability captured the attention of the Detroit Free Press—which rated him as one of the city’s best high school football players and awarded him with AllCity Third-Team honors—a season-ending injury against a robust Hamtramck team curtailed his high school football career. He suffered a vicious tackle, resulting in several torn ligaments. Track, Tolan’s least-favorite sport, proved to be the one that would propel him to international fame.

In his sophomore year of high school, he finished second place in the 50-yard dash at the first indoor scholastic meet at the University of Michigan’s (U-M) newly opened Yost Field House. He blossomed into a track phenom during the outdoor season, tying the city record in the 100-yard dash with a time of 10.2 seconds and setting a city mark in the 220-yard at 23.1 seconds. At the city finals, he won both the 100- and 220-yard races.

With what would become his trademark bandage on his left knee, along with his eyeglasses taped to the side of his head, Tolan competed against the best track stars in the state—as well as those from West Virginia, Illinois, and Ohio—at the Twenty-Sixth Annual U-M Outdoor Interscholastic Meet. He put on a brilliant performance, winning the 100-yard race in 10.3 seconds. At the Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA) championship meet, he won both the 100- and 220- yard dashes.

Tolan’s senior year witnessed continued success. He won the 50-yard run at the Third Annual Indoor Meet at U-M; the 100- and 220-yard dashes at U-M’s Outdoor Interscholastic Meet; and the 100- and 220-yard races at the MHSAA championship with times of 9.8 and 21.9 seconds, respectively.

During his Cass Tech career, the up-and-coming star compiled a remarkable, if not unmatched, track record—including a 94 percent win record in city and state individual outdoor championships. The young, scrawny African-American kid known as “Little Eddie” finished high school as one of the greatest athletes in the history of the MHSAA.

A Standout at U-M

Despite his earlier injury, Tolan was recruited by several major universities for football, in addition to track. Having secured a track scholarship to attend U-M, he joined the freshman Wolverine football squad in the fall of 1927.

On the third day of practice, Tolan was informed by a coach that “Some of [the other coaches] think that you should not be allowed to play football. I’d be tickled to have you, but I am afraid I’m going to be outvoted.” He was instructed to turn in his uniform and concentrate on track.

It is unknown whether Tolan was removed from the football team due to racial prejudice or if he ultimately opted to pursue only track to take advantage of the travel opportunities the latter sport afforded. Given Tolan’s love for football, however, it is hard to believe he simply walked away from the game. In addition, according to several accounts in U-M football history, Coach Fielding H. Yost excluded African American athletes from the team until Willis Ward joined in 1932.

Tolan turned his attention to track, running the 100- and 220-yard dashes and anchoring the 440- and the 880-yard relay teams. At 5 feet 6 inches and 130 pounds, he was well-muscled, with powerful arms and legs that worked with machinelike precision. He was also known for chewing gum while he raced. In addition to using it to relieve stress, Tolan chewed gum to monitor his speed—the faster he chewed, the faster he would accelerate his powerful legs.

Eddie Tolan sprinting for U-M's track team in 1931.

Eddie Tolan competing on the U-M track team in 1930. Image from the Michiganensian.

Although track and field offered some opportunities for athletes of color during the 1920s and 1930s, the sport was not without racism. During his time at U-M, Tolan was not allowed to eat with his European-American teammates on road trips. He was also advised not to complain about racist incidents and treatment. Complaining, he was told, would lead to him being the last African-American athlete to run for the university.

In 1928, as a sophomore, Tolan tried out for the Olympic team. He made the finals in both the 100- and 200-meter dashes at the trials but failed to make the official U.S. team. He went on to compete in track at U-M during the 1929, 1930, and 1931 seasons.

On May 25, 1929, Tolan broke the Big Ten Conference record and broke the world re(AAU) Senior Championship in July, the sprinter won the 100-yard dash in 10 seconds and the 220-yard dash in 21.9—earning him a trip to Europe with the AAU’s American team. There, Tolan equaled Olympic gold medalist Charles William Paddock’s record in the 100-meter race with a time of 10.4 seconds.

At the Big Ten championship in May of the following year, Tolan— then a junior—came in second place in the 100-yard dash behind the Ohio State University’s George Simpson, earning him the nickname “Midnight Express.”

Although Tolan experienced success as a sprinter in 1929 and 1930, it was the 1931 season—in which he dominated the Big Ten—that solidified his new nickname. He won the outdoor 100-yard dash in 9.6 seconds and 220-yard dash in 20.9 seconds at the championships. By the time he graduated from U-M, Tolan had competed in 100 races, losing only nine times. He was elected AAU All-College and AllAmerican in the 220-yard dash.

In addition to his involvement in collegiate athletics, Tolan became a member of the Black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha. By 1929, he resided at the fraternity house, located at 1103 Huron Street in Ann Arbor’s historic district. cord in the 100- yard dash with a time of 9.5 seconds. He also won the 220-yard race that day. At the Amateur Athletic Union

Eddie Tolan crosses the finish line to win gold in the 200-meter race at the 1932 Olympics.

Winning the Gold…Twice

After graduating from U-M, Tolan enrolled in graduate school at West Virginia State College, a historically black college located in Charleston. The program aimed to prepare students for teaching and coaching in America’s segregated education system. Tolan coached track at the school, which enabled him to stay in shape for the upcoming Olympics.

In July 1932, Tolan raced at the Olympic trials at Stanford University, where he finished second after his Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity brother—Ralph Metcalfe of Marquette University—in both the 100- and 200-meter dashes. The United States had suffered a 12-year drought in the 100-meter race, and Tolan and Metcalfe were viewed as the sprinters capable of returning America to international dominance in the event. Their first and second-place finishes at the trials also meant that the top two American Olympic sprinters were, for the first time, African American.

During the 1932 Summer Olympics, the Midnight Express became etched in track lore. At the Los Angeles Olympic Stadium on August 3, Tolan—his hornrimmed glasses taped to the side of his head, his left knee bandaged, and chomping a mouthful of chewing gum to the rhythm of his stride—broke the Olympic record in the 100-meter dash with a time of 10.3 seconds. The sprinter’s gold-medal-winning run was not without controversy. The end of the race came down to a photo finish between Tolan and Metcalfe, the latter of whom was originally announced the winner. After carefully reviewing the camera timer, the official judge ruled that they crossed the finish line in a dead heat—but that Tolan’s torso crossed before Metcalfe’s.

In the 200-meter run, Tolan won over George Simpson, with Metcalfe finishing third. The Michigander’s 21.2-second time earned him his second gold medal, as well as another Olympic record. With two golds, Eddie Tolan became the first double Olympic sprint champion in 20 years, and he claimed the title of “World’s Fastest Human”—the first time an African American had been given that label.

The media coverage of Tolan’s Olympic triumph, however, was marred by racism. The American media referred to him as the “dusky Negro,” “the little Black man with horn-rimmed glasses,” and “the chunky Detroit Negro,” among other phrases. Tolan’s accomplishments continued to take a backseat to racial prejudice.

Returning Home

Tolan returned to Michigan an international hero, stating his intent to give his two gold medals to his mother, Alice. Under the leadership of Mayor Frank Murphy, Detroit gave the gold medalist a hero’s welcome at the local train station. Tolan was celebrated at city hall with proclamations and speeches praising his Olympic performance—claiming that his successes would lead to improved race relations. Governor Wilber Brucker even declared September 6, 1932, to be “Eddie Tolan Day” throughout the state.

Unfortunately, Tolan’s U-M degree, graduate work, and international fame as the world’s fastest human came without compensation or lucrative endorsements. He was broke and jobless, and the United States was in the depths of the Great Depression. To an American society steeped in racism, Tolan was simply a “Negro.” During the parade and festivities celebrating Eddie Tolan Day, the decorated sprinter asked Mayor Murphy for a job but did not have luck securing one.

Short on funds, Tolan walked the streets Detroit. His mother, the family’s sole provider, once stated, “If my menfolk could only find jobs, I could ease up a bit and a mighty big worry would be off Eddie’s mind.” Desperate for any type of work, Tolan joined entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson on the vaudeville circuit. In front of eager audiences, Tolan shared the story of his rise from poverty in Detroit to Olympic success. However, Tolan was soon ruled to be in violation of amateur athletic laws for using his track fame to earn an income. The AAU stripped him of his status in June 1933.

Still, with his father and brother out of work, the family looked to Tolan to leverage his celebrity and secure stable employment. He was finally offered the low-paying position of filing clerk at the Wayne County Register of Deeds—a job he would hold from 1933 to 1935. During that period, he also attended law school at night in hopes of joining the black professional class. Tolan had no intention of running professionally after losing his amateur status. “I haven’t any complaints. I just don’t think I’ll run again,” he told The New York Times in 1933. “I’m sticking to my job.”

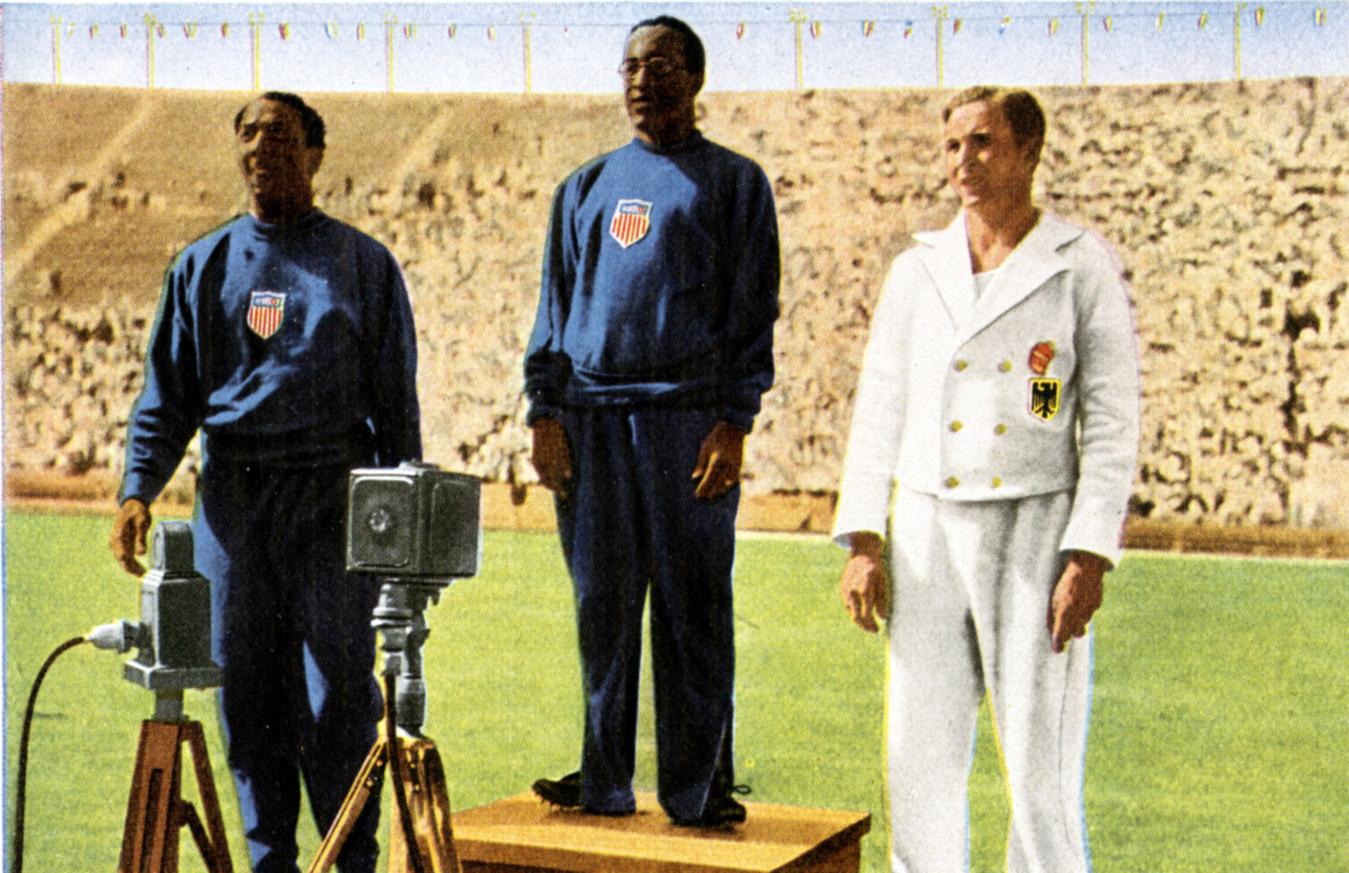

Eddie Tolan (left), Willis Ward (center), and Jesse Owens (right) shake hands at Ferry Field during the 1935 Big Ten Meet.

His mind would change a year later, however, when presented with an opportunity to run professionally in Australia and New Zealand in November 1934. He was granted a leave of absence from his clerk job, spending the next six months as a professional sprinter in Oceania. At the World Professional Track and Field Championship in Melbourne, Australia, he set a new world record in the 220-yard race. He also won the 75-, 100-, and 120-yard dashes.

Life After Track

Despite achieving international acclaim in his professional running career, when Tolan returned to Detroit in 1935, his successes still did not translate into a better-paying job. He resumed his filing position at the register of deeds. From 1939 to 1945, he found work as a stock clerk at the Detroit Packard Motor Company—which was viewed as one of the better positions for African Americans, since most were restricted to working in the foundry or in sanitation. He was employed there during what the Michigan Chronicle called the “Packard Hate Strike” of June 3, 1943, when close to 25,000 European-American workers went on strike to protest the promotion of three African Americans to the aircraft assembly line.

In 1956—after previously being denied a permanent teaching certificate due to discriminatory practices—Tolan finally secured a license to teach in Detroit Public Schools and was hired as a physical education teacher at Goldberg Elementary School. He was known throughout his teaching career as a caring, compassionate, and knowledgeable educator with a deep desire for his students to excel both academically and athletically.

Tolan would oftentimes visit with coaches and track runners at his alma mater, Cass Tech, where he offered friendly advice to the young athletes. However, despite being a track star in high school, a former collegiate coach, a two-time Olympic gold medalist, and the only sprinter to win both amateur and professional championships in history, Tolan was not allowed to coach high school track. After suffering from kidney failure, he retired from the Detroit Public School system in 1966.

On January 30, 1967—at the age of 58—Eddie Tolan’s heart failed while he underwent his weekly dialysis treatment at Mount Carmel Hospital. He was buried at United Memorial Gardens in Plymouth. His obituary noted what many came to believe about his life: “He deserved better.”

After his death, the Edward Tolan Playfield located along Mack Avenue and Chrysler Freeway was named in his honor, and he was inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1982. His medals and a pair of his shoes are on display at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit—donated by his sister, June Tolan Brown.

Olympic athlete Jesse Owens later recalled how Tolan was greatly admired in the African-American community. While Owens was in high school, Eddie Tolan and Ralph Metcalfe were his idols, and they became friends and fraternity brothers later in life. Owens also remembered Tolan’s advice for being a successful sprinter: “Start fast, run easily, stay in your lane and finish strong.”

Categories: Uncategorized